ICT is truly a transversal aspect of LLL: it affects every modality of implementation and is shaping the agenda in significant ways in terms of LLL implementation. Chapter 1 summarized the global trend of developments in digital technologies and its implications for LLL. In terms of LLL implementation, the advancement of digital technologies in recent years has opened up a new learning space, which overlaps with but is also separate to traditional learning spaces and pre-existing learning processes. This section provides an overview of how ICT can be used effectively for formal, non-formal and informal learning. It also reinforces the point made throughout this handbook that the boundaries between learning modalities are becoming increasingly blurred. In fact, this is in large part precipitated by the increased use of ICT, which extends its reach from formal and non-formal learning programmes (e.g. language courses) into informal settings (e.g. learners’ homes) and likewise brings tools for informal learning (e.g. mobile devices) into formal learning environments (e.g. schools). This section also highlights the value of interventions to promote ICT for LLL, particularly through national digital strategy development.

3.5.1. Using ICT for LLL

Here, we provide an overview of the ICTs being used across different modalities of LLL and for the benefit of particular groups. We then introduce open educational resources (OER) and massive open online courses (MOOCs) as two specific types of initiatives to widen access to knowledge and learning through ICT.

Modalities of learning

Increasing the availability and use of ICT carries advantages for all modalities of learning. In the formal sector, equipping schools with new technology opens up new worlds of enquiry and knowledge sources to pupils, whose learning quickly extends beyond the school environment even while sitting in a classroom. For universities, ICT introduces flexibility to previously rigid study programmes and makes higher education more accessible to students restricted by geography, time or other work and life commitments. By extending technology into homes and community learning centres around the world, ICT delivers and enhances non-formal learning catered to the needs of individuals and local communities. Finally, a proliferation of applications and information, available across a growing range of electronic devices, equips people with a powerful tool for informal learning by supporting unstructured literacy development, quick access to vocational information and more.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the role of ICT for learning took on new and profound significance. In schools, universities and the non-formal sector, almost all forms of learning provision moved online in a dramatic acceleration of a trend that was already evident. In recent years, ICT has become more integrated in formal schooling. In many parts of the world, it now complements a variety of subjects, topics and learning projects. In primary and secondary schools, there have been moves towards what the European Commission (2019) terms ‘highly equipped and connected classrooms’, a concept with four dimensions: digital technology equipment, network requirements, professional development of teachers, and access to digital content. According to this model, classrooms that use ICT effectively for learning can chart their course from ‘entry level’ to ‘advanced level’ to ‘cutting-edge level’. While ‘entry level’ includes considerations such as laptops for every three students, interactive whiteboards, network connectivity, online training for teachers and educational software, a classroom at an ‘advanced level’ has 3D modelling software, a digital classroom management system, online communities of practice for teachers and virtual online laboratories. Finally, with the ‘cutting-edge level’ comes laptops and e-book readers for all students, virtual-reality headsets, ultra-fast broadband, increased opportunities for face-to-face professional development and well-established access to a range of digital content (European Commission, 2019).

|

Box 3.14. LLL in practice ICT for schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic In Germany, there is a ‘Digital Pact’ between the federal and state governments to improve the use of digital technology in schools. When the COVID-19 pandemic caused nationwide lockdowns beginning in March 2020, €100 million was made available within this framework for the expansion of digital learning while schools were closed. At the institutional level, schools in Germany undertook a range of initiatives to strengthen their capacities for digital learning during the pandemic. For example, the Max Brauer School in Hamburg made use of the Schul.cloud app: teachers uploaded tasks using the app and learners then integrated those tasks into weekly schedules with specific learning objectives. Meanwhile, at the St. Josef Gymnasium in Thuringia, central Germany, the school benefitted from the strong digital credentials it had acquired prior to the pandemic: classrooms were already equipped with TVs, interactive whiteboards and projectors, while students in the Grade 9 and above were given iPads to use for learning. With the use of ICT embedded in the school’s operations, teachers and learners were able to quickly make the switch to online instruction and maintain a high quality of learning during the lockdown. Source: Robert Bosch Stiftung, 2021 |

Technology-enhanced learning can also mitigate the attendance requirements of full-time study at universities: it allows people to follow a formal course while working, enables easier delivery of materials from lecturers to students and vice versa, and connects learners to people and resources that can support their educational needs online, such as OERs.

The effective use of ICT for non-formal learning can also be seen in adult literacy and basic education programmes, which have used different technologies for decades to support adult learning and education. These include radio, television, and audio and video cassettes. More recently, digital ICT such as computers, tablets, e-readers and smartphones have spread rapidly and found their way into the teaching and learning of literacy and numeracy skills. The large spectrum of ICT includes satellite systems, network hardware and software, as well as video-conferencing and electronic mail. Each one of these technologies opens up new possibilities to develop literacy skills from the safety of one’s home and offers virtually unrestricted access to learning materials.

As the increasing ubiquity of technology encourages more and more people to make regular use of technological devices, ICT shapes informal, everyday learning in ever-expanding ways. Popular ICT-based informal learning includes podcasts and online encyclopaedias. ICT for informal learning may also include technological developments that support TVET in the informal labour market, which covers casual, temporary and unpaid work in addition to micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). Collectively, these forms of work constitute up to 95 per cent of all labour. ICT provides a medium through which those wishing to start or who are already running MSMEs can learn about good business practices. One example of this is the SME Toolkit, provided by the International Finance Corporation (IFC in partnership with IBM, an American multinational technology corporation, which is home to a wealth of information, resources and tools to boost productivity and efficiency. By March 2015, it was used by 6 million users annually and offered content in 16 languages (Latchem, 2017).

ICT for particular target groups

For refugees who have been forced into ever-changing, uncertain circumstances, ICT in the form of mobile technology carries invaluable advantages due to its portability: it can accompany refugees as they transition between locations and provide them with opportunities for informal learning in the process. Mobile technology supports refugees’ learning with access to digital resources in situations where the transportation of printed materials is not feasible. A major advantage is seen in the capacity of mobile devices to support refugees in learning the language of their host country.

For learners in rural areas, ICT can support literacy learning. This is particularly the case when ample quantities of digital devices are available and accessible to local people and when digital learning programmes satisfy their learning needs and interests. An example of such a literacy initiative is the Talking Book project. Led by the NGO Literacy Bridge, Talking Book has been implemented among communities of farmers in Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda. With low-cost, programmable computers containing over 100 hours of audio content – including instructions, interviews, stories and songs – learners develop their literacy skills and acquire new knowledge about agriculture and healthy livelihoods at the same time (UNESCO and Pearson, 2018).

Initiatives to widen access

Technology extends traditional campus-based college and university services to distant (off-campus) and online modes and has formed the basis of distance education for many years. A common approach is ‘blended learning’, whereby physical attendance and online learning complement one another, increasing the number of learning opportunities available to different communities.

- Open educational resources

Open educational resources (OERs) are defined by UNESCO as ‘teaching, learning and research materials in any medium – digital or otherwise – that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions’ (UNESCO, 2022a). In 2019, the UNESCO General Conference adopted a Recommendation on Open Educational Resources (OER), which includes five areas of action for the use of OERs: building capacity, developing policy, encouraging inclusion and equity, creating sustainability models and promoting international cooperation (UNESCO, 2019). OERs provide opportunities for technology-enhanced learning, which in turn mitigates attendance requirements of full-time study at universities by allowing people to follow a formal course while working, enables easier delivery of materials from lecturers to students and vice versa, and connects learners to people and resources that can support their educational needs online.

In Africa, the African Health OER Network, established by health experts, features materials for health education. Using this digital resource, institutions working in the field of health science in Africa can upload materials to support health professionals, students and educators in their learning, thus helping practitioners and researchers advance their knowledge (Hezekiah University, 2018). Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, meanwhile, has developed an OER similarly aimed at health-related education but with a focus on sanitation and clean water. The OER offers courses on clean water technology, targeted at developing countries and subsequently updated with context-specific information on water treatment by universities across Indonesia, South Africa, Singapore and the Antilles (ibid.).

OERs make an important contribution to lifelong learning: they enable people of all ages to access tools to enrich their lives and find out more about the world (UNESCO, 2019). Recently, they have been used to support the shift to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic (OER4Covid, 2022).

- Massive open online courses (MOOCs)

MOOCs accommodate unlimited participation and open access via the web. In addition to traditional course materials such as pre-recorded lectures, readings and problem sets, many MOOCs provide interactive options, including forums to support interaction among students, professors and teaching assistants, as well as immediate feedback on quick quizzes and assignments.

Early MOOCs often emphasized open-access features such as the open licensing of content, structure and learning goals, and promoted the re-use and remixing of resources. Some later MOOCs used closed licenses for their course materials while maintaining free access for students. MOOCs address issues that have a direct impact on learners’ lives; however, there are limitations to MOOCs, including low retention and completion rates. Furthermore, with the growing tendency of providers to charge fees, the idea of extending free learning opportunities to large numbers of learners – the original raison d’être of the MOOC – has been compromised. Attention has recently shifted somewhat towards the small private online course (SPOC), which has been regarded by some institutions as a more manageable alternative to the MOOC (Symonds, 2019). Nevertheless, MOOCs remain a relatively recent and widely researched development in distance education and a form of ICT for both formal and non-formal learning.

3.5.2. Promoting the use of ICT for LLL

While the potential of ICT to transform learning is evident, without targeted policy intervention there are limitations. This is especially true for older generations, who may find it difficult to keep up with advancements in technology and are therefore at risk of being left behind. In addition, a lack of literacy skills is often connected to poverty, which may restrict access to and efficient use of technologies. Moreover, despite the seeming omnipresence of smartphones and personal computers, access to the internet is restricted in many parts of the world and particularly in rural areas.

These barriers and challenges highlight the importance of initiatives that guarantee the inclusivity of ICT for lifelong learning. Initiatives and policies that promote ICT for lifelong learning tend to address one of two areas (or both): digital infrastructure and digital skills. Both are necessary to enhance and widen access to learning.

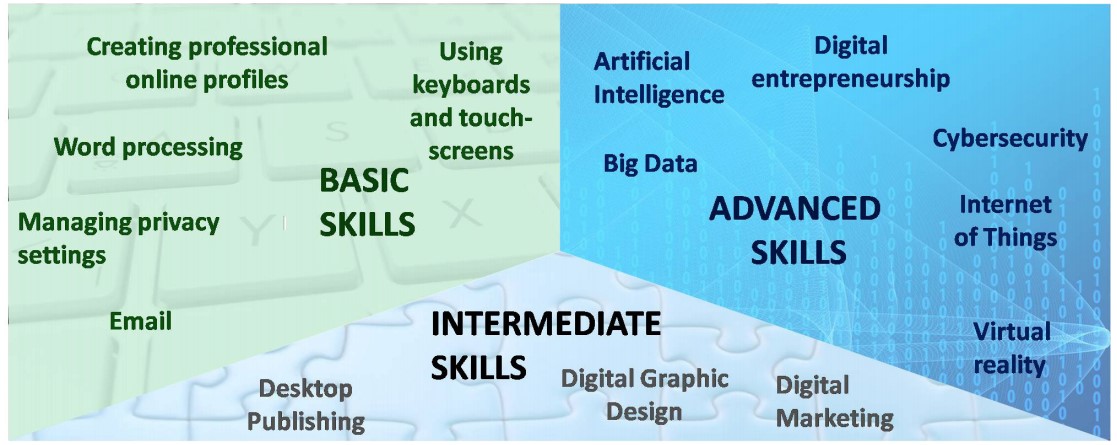

Digital infrastructure establishes the foundations for digital skills to thrive and, because it is defined mainly by physical infrastructure and telecommunications networks, it does not fall within the remit of education policy. Nevertheless, stakeholders and policy-makers in the fields of education and lifelong learning should be cognizant of its importance and advocate for its development (UNESCO, 2018a). Digital skills, meanwhile, can be categorized in many different ways and, similar to literacy skills, are located on a continuum of learning. Figure 3.2 features a simple typology of basic, intermediate and advanced digital skills.

Figure 3.2. Digital skills levels

Source: ITU, 2018

In Chapter 1, we provided the example of the African Union’s Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa (2020–2030) to show how a regional ICT strategy can respond to the global trend of digitalization. Within the realm of education policy, producing a strategy or ‘master plan’ for ICT use in education clarifies national priorities. Such documents may address technological infrastructure development within schools, but they also drive digital skills forward by advocating for teacher-training in ICT and for digital technologies to become more embedded into learning curricula. However, a strategy or master plan can only be formulated and realized if there is strong political will and coordination (UNESCO, 2018a). For example, in England, UK, there is a national strategy for the use of technology in education which aims to ‘support and enable the education sector in England, UK, to help develop and embed technology in a way that cuts workload, fosters efficiencies, removes barriers to education and ultimately drives improvements in educational outcomes’ (Department for Education, 2019, p. 5). Furthermore, this strategy proposes strengthening collaboration between the education sector and the education-technology business sector, particularly when providing technological products for education (ibid., p. 32).

|

Box 3.15. LLL in practice Singapore’s ICT master plans in education In Singapore, ICT-in-Education Masterplans have been renewed every five years since the first one was produced in 1997. The master plans include digital infrastructure for schools, equipping teachers with digital skills so that ICT is incorporated into teaching methods and, comprehensively, the acquisition of digital skills at every educational level. The desired outcomes are that students will become more adept at using technological devices to access, interpret and evaluate information and thus be better equipped to adapt to emerging professions in an increasingly digitalized economy. With these overall objectives, Singapore’s master plans facilitate instrumental, structural/informational and strategic digital skills (UNESCO, 2018a). With the conclusion of the second master plan, which was implemented between 2003 and 2008, reported achievements included increased student and teacher competences in the use of basic ICT tools (including the internet), as well as the availability of a flexible network for schools to experiment with new technologies. ‘Masterplan 3’ maintained the same vision as the previous two and ‘Masterplan 4’ focused on quality learning before being replaced by the Educational Technology (EdTech) Plan in 2019 (Ministry of Education Singapore, 2021).[1] |

3.5.3. ICT in LLL implementation strategies

As ICT plays a prominent role across all modalities of LLL implementation and is found increasingly in all learning spaces, it should be taken into consideration during the design of any LLL implementation strategy, as shown in Table 3.5.

Table 3.5. Key considerations for LLL implementation strategies – ICT

|

National ICT strategies |

|

|

Digital inclusion |

|

|

Digital skills programmes[2] |

|

|

Stakeholder cooperation for a holistic implementation strategy |

|

[1] An overview of all four master plans can be found at: https://www.moe.gov.sg/education-in-sg/educational-technology-journey.

[2] The information in this section on basic, intermediate and advanced digital skills is informed by the International Telecommunication Union’s Digital Skills Toolkit (ITU, 2018).

Advancing ICT for lifelong learning

Department for Education. 2019. Realising the potential of technology in education: A strategy for education providers and the technology industry. [PDF] London, Department for Education. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/791931/DfE-Education_Technology_Strategy.pdf [Accessed 26 ebruary 2021].

Hezekiah University. 2018. Open Educational Resources. [online] Umudi, Hezekiah University. Available at: http://hezekiah.edu.ng/OER/2018/09/23/hello/ [Accessed 2 July 2021].

Latchem, C. ed. 2017. Using ICTs and blended learning in transforming TVET. [PDF] British Columbia and Paris, COL and UNESCO. Available at: http://oasis.col.org/bitstream/handle/11599/2718/2017_Latchem_Using-ICTs-and-Blended-Learning.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 21 April 2020].

Ministry of Education Singapore. 2021. Educational technology journey. Available at: https://www.moe.gov.sg/education-in-sg/educational-technology-journey [Accessed 23 February 2022].

OER4Covid, 2020. About. [online] Available at: https://oer4covid.oeru.org/ [Accessed 2 July 2021].

Robert Bosch Stiftung. 2021. Apprentissage numérique : les écoles à l'ère du Corona [online] Stuttgart, Robert Bosch Stiftung. Disponible sur : https://www.bosch-stiftung.de/en/story/digital-learning-schools-age-corona [Accessed 2 April 2022].

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and Pearson. 2018. A landscape review: Digital inclusion for low-skilled and low-literate people. [PDF] Paris, UNESCO. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261791 [Accessed 20 April 2020].

UNESCO. 2018a. Building tomorrow’s digital skills – what conclusions can we draw from international comparative indicators? [Online]. Paris, UNESCO. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261853 [Accessed 20 April 2020].

EQUALS and UNESCO. 2019. I’d blush if I could. Closing gender divides in digital skills through education. Paris, EQUALS and UNESCO. [PDF] Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367416/PDF/367416eng.pdf.multi.page=1 [Accessed 31 January 2022].

UNESCO. 2022a. Open educational resources (OER). [online] Paris, UNESCO. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/themes/building-knowledge-societies/oer [Accessed 2 July 2021].