In 2012, the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning brought the discourse on learning cities to the international level and established the UNESCO GNLC. The UNESCO GNLC opened to membership application in 2015 and has now engaged more than 200 learning cities around the world. The network supports cities in developing holistic and integrated approaches to LLL, recognizing the needs of all learners, and enhancing access to learning for marginalized and vulnerable groups. It promotes policy dialogue and peer learning among members, fosters partnerships, builds capacity, and develops instruments to encourage and recognize progress in building learning cities. In 2015, the UNESCO GNLC published the Guidelines for Building Learning Cities (UIL, 2015b), a set of actionable recommendations in six areas that can be applied at every stage of the process of becoming a learning city: planning, involvement, celebration, accessibility, monitoring and evaluation (M&E), and funding.

The rest of this chapter uses the UNESCO GNLC as a teaching case to demonstrate how this handbook’s information, ideas and advice on LLL policy-making and the design of LLL implementation strategies at the national level can be applied practically. By focusing on the local level, this teaching case demonstrates that national LLL development both relies on and is informed by developments at the local level.

|

Box 4.1. The City Beta story Let us imagine a city, maybe near to you and with some similarities to your own city. Why would you want to develop it as a learning city? We will call this city ‘City Beta’ and try to map the City Beta route to sustainable development as an example of how the learning city approach can work. |

4.2.1. Identifying and diagnosing a public policy issue

As explained in Chapter 2, a key initial process in the design of any public policy is to define the issue being addressed. This is fundamental to identifying and communicating the reasons behind implementing a programme or intervention, as Bardach (2000) points out. A clearly defined problem includes a diagnosis of its causes, the expected changes and the potential characteristics of any intervention. Since governments face a multiplicity of challenges associated with contexts and characteristics of their communities, defining specific issues to be addressed by the learning city model could be a complex task. Local governments represent the closest level of governance to the people and are therefore the best link between global goals and local communities.

In this section, we outline three public policy issues to exemplify some of the priorities for LLL policies and their implementation: (1) urbanization, climate change and health risks; (2) the deepening of social inequalities; and (3) unemployment and lack of economic development.

|

Box 4.2. The City Beta story How will we go about identifying the challenges of City Beta? To properly understand the policy issues, we will need to consult widely within the city, talk to the leaders of the different institutions (environmental, legal, health, education, business and industry, social services, cultural, technological, NGOs) and utilize the research capabilities of the local university to analyse the data. Once we have the data evidence about the city, we can focus on the three public policy issues: (1) urbanization, climate change and health risks; (2) the deepening of social inequalities; and (3) unemployment and lack of economic development. For this exercise, we will invent the data evidence for City Beta. We must also remember to acknowledge the great things about City Beta: its fantastic sense of community and compassion towards strangers, particularly those in need, which is rare to find. |

Urbanization, climate change and health risks

The rapid expansion of cities presents new problems related to sustainable development. It is estimated that, by 2030, the proportion of the world’s population living in urban areas will increase to 60 per cent, compared to 55.3 per cent in 2018 (UN DESA, 2018). The urbanization trend is not only reflected in the rising number of people living in urban areas but also in the increased number of megacities – cities with 10 million inhabitants or more – which is expected to rise from 33 in 2018 to 43 by 2030 (ibid.). This expansion will result in hazards to be addressed by local governments, particularly those related to pollution and health.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) stressed the need to invest in health and well-being as a precondition for equitable, sustainable and peaceful societies, with particular attention to gender inequalities, groups at the highest risk of vulnerability, children’s health, and linking good health to optimal social functioning (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2017 and 2018; Watson and Wu, 2015). Local communities face challenges related to pollution, climate, health, and a combination of all three. As a result of the COVID-19 outbreak, many of the UNESCO GNLC members have faced severe challenges, including a record number of children and youth not attending school or university because of temporary or indefinite closures mandated by governments in an attempt to slow the spread of the virus. The COVID-19 pandemic and its effects will continue to dominate public policy issues for learning cities for years to come.

|

Box 4.3. The City Beta story City Beta is a coastal city where there is a small risk of flooding in the lower areas near to the river estuary in the east. There is recent urban development in this area, populated by a low-skilled, poor, mainly unemployed local community and migrants. Sanitation is adequate in the area provided there is no flooding. The river is polluted by fertilizer run-off from farming activities upstream and has a tendency to flash flood after storms, so east side residents are supplied with sandbags in case this happens. A large company on the bank of the estuary just outside the city boundary is using fossil fuels in its production process and creating air pollution. Solutions to these problems are not simple – the city needs the food that comes from the farming activities, the jobs created by the large company and to safely house the migrants, who are welcome and contribute in many ways to City Beta. How can learning possibly help with these major challenges? The COVID-19 pandemic will exacerbate the inequalities in City Beta and the east side will suffer a far higher percentage of cases than the west side. This may be due to overcrowded and multigenerational homes, less local health service provision or a lack of understanding of prevention measures. The health services in City Beta will be under great pressure and better health education for prevention and infection control will be required. Although there is good mobile phone service across the city, the internet service is better on the west side due to investment in the business district by a large internet provider. |

As stated in a recent UN-Habitat World Cities Report, ‘at this current moment of rapid urbanization and fast-paced technological change in the context of ecological and

public health crises amidst deep social inequalities, cities remain the linchpin to achieving sustainable development and meeting our climate goals’ (UN-Habitat, 2020, p. 180). The report also highlights that ‘for more than two-thirds of the world’s urban population, income inequality has increased since 1980’ (ibid., p. xvii). To ensure equitable and inclusive learning opportunities for all, learning cities must address all forms of exclusion, marginalization and inequality in education in terms of access, participation, retention and completion. Learning cities also need to take concrete actions to end all forms of gender discrimination.

Another issue related to social inequality is the ageing of society. Intergenerational exchange is important to ensure social cohesion across all ages. Efforts are also needed to help fight isolation and exclusion. In both cases, involving local governments and communities by adopting the learning cities model would present an opportunity to address prevailing social inequalities.

|

Box 4.4. The City Beta story City Beta has an ageing society and recognizes the impact this is having on its labour market. This is made evident by the recent shortage of tradespeople such as builders, carpenters, electricians and plasterers, as the existing workforce in these trades are nearing retirement age. The ageing population is also having an impact on social care and there is a shortage of carers across the city. The people in City Beta are known for their compassion and City Beta welcomes migrants and refugees, recognizing also that they may provide a solution to labour shortages. However, the data reveals that City Beta is a city of two halves, with as much as 10 years’ difference in life expectancy between the east and west sides. Investment in schools has historically been unbalanced due to greater political pressure from citizens on the more affluent west side, meaning that children on the east side must travel longer to attend a good-quality school. Attendance records show that children living on the east side are at far greater risk of becoming NEET (not in education, employment or training). The Further Education College is also on the west side, although it does provide a few apprenticeship opportunities across the city, which mainly attract boys. The university has very few admissions from the east side communities; however, it is planning to implement initiatives to address this. Moreover, it has been forced to cease its adult education programmes due to financial constraints. There is a limited programme featuring languages and crafts for adults provided by the Further Education College, and some arts and culture lifelong learning classes are run by the municipality; the latter mainly attracts attendees from the west side. This is in line with national trends, where it has been found that those who already have participated in further and higher education are more likely to engage in lifelong learning. |

Unemployment and weak economic development

One of the main challenges for local and national governments is guaranteeing access to employment opportunities. Although several factors are commonly cited to explain unequal distribution of labour opportunities, one that is particularly relevant to cities is the surge in migration to urban areas from rural ones, where ‘the majority of the global poor live’ (World Bank, 2020). These migrants are ‘poorly educated, employed in the agricultural sector, and under 18 years of age’ (ibid.). Taken together, these circumstances strengthen the incentive to migrate to urban regions. Keep in mind, however, that the exact nature of unemployment will depend on the specific challenges a city faces.

These three public policy issues – (1) urbanization, climate change and health risks; (2) the deepening of social inequalities; and (3) unemployment and lack of economic development – represent priorities to be pursued by adopting the UNESCO GNLC model. As a LLL policy, this model aims to create learning opportunities for all, in formal and non-formal contexts, engaging different stakeholders, and exploring the participation of different agencies and organizations.

|

Box 4.5. The City Beta story There is high unemployment in City Beta’s east side communities. Potential employers complain of a lack of soft skills and work ethic in relation to local unemployed people. New migrants to City Beta tend to come from rural areas and are keen to work but lack technological skills, while refugees often have language needs. A scarcity of employment opportunities in rural areas is the main reason for migration to City Beta at present. At the same time, employers in City Beta are reporting skills shortages, particularly in the new call centre industries, which require some technological understanding and a range of soft skills. Migrants are keen to learn new skills, but it is a long way to the Further Education College across the city on the west side, with unreliable and expensive public transport routes. Employers complain that the curriculum in further and higher education does not meet their skills needs. The large company on the bank of the estuary has just announced major redundancies due to global competition. A new employer running a call centre operation is considering expansion in City Beta but is seeking assurance that the skills it requires will be available. |

4.2.2. Design and implementation: What are the required policy innovations?

Following the policy-making process set out in Chapter 2, once a public problem has been defined, the next steps are to design policy innovations and implement initiatives.

Focus areas for learning cities

In the case of the learning cities model, which is based on problem detection and definition, six different ‘focus areas’ have been promoted and will be expanded on here. They include several learning environments (educational institutions, family, community, workplace, online learning), aim to increase accessibility to and participation in learning for all groups of society (‘inclusive learning’), and address the conditions and motivation for lifelong learning (‘culture of learning’).

We will explore each focus area in relation to policy innovations which inform the implementation of LLL in cities. Many of these points relate back to the areas of LLL implementation covered in Chapter 3.

1. Promoting inclusive learning from basic to higher education and beyond.

Cities can promote inclusive learning in the education system by expanding access to education at all levels, from early childhood care and education (ECCE) to primary, secondary and tertiary level, including adult education and technical and vocational education and training (TVET). Furthermore, cities can support flexible learning pathways by offering diverse learning opportunities that meet a range of proficiencies. To ensure access for all inhabitants of the city and its surroundings, support should be offered to marginalized groups in particular, including migrant families.

As shown in Chapter 3, there are many potential interventions to promote inclusive learning at all levels, across formal, non-formal and/or informal learning modalities. As specific policy goals and interventions need to be determined at this stage, it is important to focus on the areas of jurisdiction cities have in the education system. For example, in the case of formal education, it is less likely that cities will have direct control over curricula or teacher training, but they might have some responsibility for the management of educational buildings and general infrastructure, including the authority to open up school buildings after hours so they can be used by the local community, as described in Chapter 3. When it comes to non-formal education, the city may have some jurisdiction over ECCE, facilitator training or basic education curricula, and so these aspects could be addressed by a planned intervention with specific policy goals.

While many interventions to promote inclusive learning in cities through the learning city model are devised by municipal governments, higher education institutions (HEIs) also make valuable contributions and often support learning city development actively. In both aspiring and established learning cities, stakeholders in local HEIs often drive the learning city process or advise municipal governments and provide valuable resources. Though the extent of HEIs’ involvement varies from city to city, important contributions are made in terms of strategy, planning, coordination and implementation. These efforts are often tied to the HEIs’ ‘third mission’ of LLL which, as explained in Chapter 3, can also lead to an expansion of flexible learning programmes for non-traditional students.

|

Box 4.6. The City Beta story In City Beta, it was apparent that the distribution of educational opportunities was inequal, as the schools, college and university are on the west side of the city and public transport is inadequate. The university undertook social science research in the city and was concerned by the resultant data and by the educational limitations of the few university applicants from the east side. In response, the vice chancellor called a meeting of all education providers in the city, including formal and non-formal learning institutions (see Chapter 3), to create the City Beta Learning Partnership (C3LP). The C3LP members soon realized that they also need to include representatives from employers, the voluntary sector, health sector, NGOs and careers services in the partnership. It was recognized that a consultation with community representatives was also needed. The university held a forum where the data evidence about the city was presented and all present agreed that solutions needed to be found. Current provision and progression pathways were mapped, and gaps identified. Employers formed subgroups according to sector and provided accurate information about the current skills that were needed for their sector. Moreover, the city managers understood that the distribution of resources needed to change and so, when funding for a new primary school was agreed on, it was decided that it would be built on the east side. Culturally, there City Beta has a thriving music scene, a museum, theatre and art gallery, and it holds an annual carnival that attracts many tourists. City Beta decided to link the municipality’s lifelong learning classes to these cultural opportunities, encouraging students to attend the theatre, visit the museum and art exhibitions, and to participate in the carnival. |

2. Revitalizing learning in families and communities.

The family is an especially important setting for informal learning, a key activity to modify some of the social behaviours affecting communities. In addition, learning in families and local communities reinforces social cohesion and can improve the quality of life for all members of society. Lifelong learning should not be confined to educational or business settings, and particular attention should be given to vulnerable groups, including those affected by poverty, people with disabilities, refugees and migrants. An example of expected interventions may be observed in Nzérékoré, Guinea, where city-led initiatives provide inhabitants with opportunities to learn more about protecting their environment and preserving public hygiene: a wide-reaching waste management project has engaged local people and created job opportunities for vulnerable groups (UIL, 2017).

Chapter 3 provided many examples of learning in families and communities. Non-formal and informal learning initiatives such as family learning and study circles can feature in interventions designed by cities. Similarly, cities can support local institutions that foster learning in families and communities, such as community learning centres (CLCs) and public libraries. During the COVID-19 pandemic, cities have played an active role in promoting learning for public health and hygiene in local communities, demonstrating the impact of cities’ interventions in this focus area. In Mayo-Baléo, Cameroon, a partnership was established between the municipal government and a local support network for the dissemination of information on COVID-19, and, in São Paulo, Brazil, the municipal government organized an emergency school meals programme when education was disrupted by the pandemic (UIL, 2021). By considering these options, specific policy goals and interventions can revitalize learning in families and communities.

|

Box 4.7. The City Beta story In City Beta, a consultation with community representatives from the east side revealed the need for more local adult learning provision, but it was not clear how engagement with learners would be achieved. The C3LP held sessions in the shopping mall with the support of community learning centres, where citizens could speak to providers about their learning needs. There was a poor response from citizens living on the east side; it was therefore evident that a different approach was required. Having supported this exploratory outreach activity, the community learning centres involved in the C3LP approached their university partners with initial findings. The university then enlisted social scientists to consult with east side residents in local cafes and other usual meeting places within the community. It became apparent that a ‘parachuting in’ approach would fail and that the desire for learning needed to come from the community itself. How could this be achieved? Fortunately, as a result of the consultation, an East Side Women’s Group became interested in the possibility of local adult learning classes and decided to take preemptive action. They identified a health practice building that had been left vacant when the new health centre was built. By approaching the health board and proposing their plans for the building, the women managed to secure it at a nominal rent, to renovate as a location in the community for learning to take place. The actual renovation work, undertaken by volunteers from the community, functioned as a learning activity and created a sense of community ownership. The building needed some investment to make it accessible and the municipality provided some funds, to be reimbursed by renting space in the building to learning providers. Importantly, the municipality also provided expert advice from its surveyors and planning department. This model worked well, and the building was soon opened and fit to hold classes. At first, the classes were poorly attended. It became clear that the curriculum needed to be negotiated with the community. This exercise was also undertaken by social scientists from the university and teachers of adult learning classes in the community learning centres. The most popular choice of course for the east side’s adult residents was ICT – perhaps because it was easier to claim that ICT was not available when they attended school than it was to admit to a need for help with literacy. When a local internet provider donated free internet in the learning centre, a local employer could see the potential of the learning centre as a source of new employees and started to provide ICT skills classes. Classes related to homemaking, such as cooking and sewing, soon began, followed by craft classes such as carpentry, spinning and weaving, and basic home maintenance. Although classes were free for all to attend, after the first flush of interest, women became noticeable by their absence. Without childcare provision, the mothers were finding it hard to attend, so a crèche with high-quality facilities was developed in the centre by the Women’s Group, improving ECCE in the area. At the same time, the Further Education College used the crèche to provide work experience as part of the training for new ECCE workers and some local women began the training course. The first classes leading to qualifications provided in the centre were childcare, child development and care for the elderly. The use of recognition, validation and accreditation (RVA) and credit accumulation and transfer (CAT) were adopted (see Chapter 3). Space was allocated for a kitchen, which was open to the public and provided a canteen for learners and staff. The kitchen was also used as a training kitchen by the Further Education College. Learners reported that their participation in classes was changing the attitudes of their children to learning, because they could see their parents or carers setting an example. Finally, in response to community demand, higher education access classes were developed; books were provided by the city library to support adult learning and access classes. Eventually a small branch library was opened in the learning centre. This process did not happen overnight, but a few important lessons were learned:

During the COVID-19 pandemic, health education classes and emergency food parcels to replace school meals were provided by the centre, making it an important focal point in the community in the time of crisis. |

3. Facilitating learning for and in the workplace.

Providing appropriate learning opportunities for all members of the workforce as well as unemployed youth and adults is of particular importance for any learning city. Due to globalization, technological advancement and the growth of knowledge-based economies, most adults need to update their knowledge and skills regularly. Private and public organizations must embrace a culture of learning to respond to specific demands from different populations looking to improve their employability. Flexible learning pathways may support people’s transitions between education and employment in cities.

|

Box 4.8. The City Beta story City Beta had the prospect of a major redundancy, with the type of manual skills required in the heavy industry not being needed elsewhere in the region. This posed a huge challenge for the city, as the mainly male and middle-aged workforce needed a lot of support to change careers. The first stage was for the City Beta Learning Partnership (C3LP) to provide adult guidance for these workers, so that they were well informed about future job opportunities and the new skills that would be needed. A shortage of tradespeople was reported in the city and a skills analysis revealed that many of the redundant workers had informally developed skills related to trades, such as plastering, carpentry and electrician skills, and general building work. A programme of training combined with the RVA of these skills was offered by the Further Education College and a ‘Fast Track to the Trades’ initiative was developed. Understanding that no similar jobs to those lost were available, many of the redundant workers took the training opportunities and the immediate pressure on trades supply was lessened. There was, however, a gender imbalance in the trades, so this initiative was combined with a strategic increase in the number of apprenticeships funded by the Further Education College combined with a drive to engage girls in taking up these apprenticeships. A major City Beta employer was having difficulties in recruiting software engineers and considering relocation to another city where the skills would be available. The employer approached the C3LP for advice; the university and some CLCs agreed to provide an intensive training programme, including RVA, for adults who wished to change careers to become software engineers. The training programmes were so successful that they were advertised across the city as evening classes as well as intensive courses over a few months for unemployed graduates and highly skilled refugees. The programmes allowed for flexible learning using credit accumulation and transfer (CAT), which meant that women in particular could take time out for family reasons and then return to learning. Soon, a pool of highly skilled software engineers was available, and the employer was able to fulfil their requirements. The availability of a surplus of these skilled workers attracted other employers to relocate to the city, and a strong IT sector began to form in the city centre. The tech employers worked with the university to develop an annual Tech Festival, which attracted further tech businesses to relocate to the city. |

When defining policy goals and interventions to facilitate learning for and in the workplace, it is advisable for cities to work in close collaboration with local employers and partners. The practices of some member cities of the UNESCO GNLC have shown different possible ways of collaborating with local employers to facilitate learning for the workplace. These include provisions related to education and training, such as offering training programmes for young people and adults who are out of education and training to gain or upgrade their skills; vocational training and skills development with local industries where job opportunities exist; and providing professional development opportunities for educators and trainers in order to embed entrepreneurial knowledge and skills in formal and non-formal learning (UIL, 2017a).

There are other innovative approaches to providing support and mentor-based provisions for the community; for example, by facilitating ongoing support to help adults find and retain employment, developing schemes to align school-based career guidance with support for businesses that offer students on-the-job training, and providing workshops and mentoring programmes to promote entrepreneurship among women and vulnerable groups such as ethnic minorities, migrants, lower socio-economic groups and those living in remote rural areas (ibid.).

Some member cities of the UNESCO GNLC also promote learning in the workplace by collaborating with local employers and partners. These initiatives can range from establishing flagship programmes to develop the leadership and entrepreneurial skills of business owners and managers, to partnering with local universities to formulate university-industry campuses that support entrepreneurship and the commercialization of research-led opportunities (ibid.)

|

Box 4.9. The City Beta story The C3LP was concerned about the impact of mass redundancies. An analysis by the university revealed that the city’s employment was too dependent on a few large employers and the public sector. The C3LP had seen how the tech sector had developed and decided to nurture other new enterprises that would each employ a small number of staff but would collectively be an important employment sector. Importantly, if the new enterprises were ‘homegrown’, it was anticipated that they would stay in the city and employ local people as they grew. It was also hoped that new opportunities for enterprise would help the city to retain talent, as highly skilled and creative young people tended to migrate away from City Beta. The partnership agreed to develop entrepreneurial learning across all formal and non-formal education and training. The provision of support, training, finance and premises for new enterprises was mapped and gaps identified. The university and the Further Education College provided students to assist with developing enterprise skills from an early age in primary schools. The employers in the C3LP saw that the skills and attitudes they required were the same as those developed by entrepreneurial learning, so they were supportive and sponsored enterprise competitions. The initiative was very successful: and as well as the tech sector, a creative industries sector soon developed in the city centre, taking over redundant retail space and employing college and university graduates. Seeing the beneficial impact of these burgeoning sectors, the university developed enterprise support for health tech innovations, leading to a third nascent sector and attracting additional research funding. |

|

Box 4.10. LLL in practice Preparing young people for employment The city leadership of Bristol, UK, has made a commitment to provide work experience placements and apprenticeship opportunities for every young person in Bristol who wants one. This commitment has been formalized with its inclusion in Bristol’s wider strategic vision. A delivery partner has been commissioned to lead WORKS, a unique collaboration between employers, learning providers and local communities to develop a skilled local workforce. WORKS connects businesses and educators to develop better and more coordinated work experience opportunities and to help young people find employment through a number of schemes, including apprenticeships. Source: UIL, 2017 |

4. Facilitating and encouraging the use of digital learning technologies.

Information and communication technology (ICT) has opened up many new possibilities for education and learning, in particular by widening access to learning materials, enhancing the flexibility of time and place, and meeting learners’ needs. Learning cities should therefore promote the use of these technologies for learning and self-empowerment.

The value of ICT to LLL is detailed in Section 3.5 of Chapter 3, and all the areas addressed there apply to learning cities. With urban environments typically home to high levels of internet connectivity and technological development, there are many opportunities to promote the use of ICT for formal, non-formal and informal learning in cities. Furthermore, learning cities have an obligation to counter any digital divide that may be prevalent at the local level, in terms of both infrastructure and schools. This means ensuring access to ICT for people living in deprived areas, as well as facilitating digital skills programmes for vulnerable groups.

The challenges associated with living in a digital age, where technological advancements are rapidly progressing, widely affect older generations, who struggle the most to meet the increasing skill demands required of a digitalized society. An initiative in Shanghai, China, supports the ICT skills development of its older population by using a large-scale distance learning programme comprised of independent online courses and live online classrooms hosted by teachers across different districts. The course content was tailored to the learning needs of Shanghai’s older citizens through an in-depth analysis (UIL, 2021).

An increasing number of cities are integrating ICT for LLL into their strategies for learning city development, such as Fatick in Senegal, which promotes digital literacy and offers virtual classes.

|

Box 4.11. The City Beta story The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the inequal access to technology and the internet across City Beta, particularly in the disadvantaged communities on the east side of the city. In response, an emergency online meeting of C3LP members was called, and the gravity of the situation was outlined by the municipality’s director of education. Many children did not have access to a device or the internet in their homes, so while all the schools were closed, they had no access to learning. The municipality had made immediate arrangements for the distribution of food parcels to children and families in need, but the situation regarding access to online learning was seemingly impossible to solve. Immediately the C3LP partners offered solutions. Because the universities replace their computing equipment every three years, a store of redundant equipment could be distributed to families who lacked home computers. Schools managed the distribution and local employers, seeing the public relations opportunity, donated additional devices. Tech companies in the city offered to sponsor mobile dongles for the children due to sit exams that summer, providing internet access so that they could continue to study at home. Community learning centres provided their classes online for free. Nevertheless, the problem of internet access remained for residents on the east side, where the internet service was unreliable. The C3LP team approached the major internet provider who supplied the three largest companies in the city and asked for help. As a result, internet was provided free to all the communities on the east side of the city and to individual families identified by the schools as being in need. Furthermore, a website was created where all online lessons and materials could be hosted. C3LP members agreed to share the task of putting classes online so that each teacher took responsibility for the topics they were most enthusiastic about teaching; the whole secondary curriculum was rapidly made available in this way. Primary teachers held online sessions with children so they could provide home schooling and, at the same time, check that children were safe and well. The lockdowns brought by COVID-19 were particularly challenging for older adults enrolled in lifelong learning programmes in both formal and non-formal learning institutions, as many of these learners lacked the skills or knowledge to ‘go online’. To respond to this situation, many institutions set up a telephone helpline and coached each caller individually, whether they wanted to go online for shopping, meeting family or for learning. This service, combined with a strategic decision to make all classes free during the pandemic, resulted in a vast increase in lifelong learning class registrations. |

5. Enhancing quality and promoting excellence in learning.

In developing learning cities, emphasis should be placed on enhancing quality in learning. This can be achieved with a paradigm shift from teaching to learning and by moving from the mere acquisition of information to the development of creativity and learning skills. It also relates to raising awareness of shared values and promoting tolerance of difference. Employing appropriately trained administrators, teachers and educators is another key element to meet the diverse learning needs of children, youth and adults.

Cities that mainstream LLL in their development have an active role to play in enhancing quality of learning. This is particularly the case for non-formal learning, as cities tend to have more influence in the local implementation of non-formal education than they do in the formal education sector. Though the situation varies depending on national and local contexts and governance structures, cities are likely to exercise jurisdiction in several important aspects of non-formal education, contributing to such areas as the management of local learning centres, local libraries’ interventions for youth and adult literacy, facilitator training and curriculum design for basic education, and funding for local learning programmes. Policy goals and interventions aimed at enhancing quality and promoting excellence in learning should therefore consider the role of the city in non-formal education.

|

Box 4.12. The City Beta story There are international measures that compare educational outcomes of young people, and the City Beta Learning Partnership was concerned that the results for City Beta school students were not at all satisfactory. They therefore agreed to run a ‘Quality in Education’ project comprising several components, including buildings and infrastructure, teacher training, and the development of a ‘twenty-first century’ curriculum. The municipality contacted the national government with its ambitious plans and was allocated funding for the refurbishment of all schools. The municipality also had sufficient funds for a new secondary school, and it was agreed that this should be built on the east side of the city. A local college specializing in TVET developed new programmes of teacher education, which focused on delivering the experiences, knowledge and skills that young people need for employment, lifelong learning and active citizenship. The ‘twenty-first century’ curriculum was designed by teachers working together and is intended to guide learners who are ready to learn throughout their lives; be healthy, enterprising and creative individuals ready to play a full part in life; and work as global citizens of City Beta. It was agreed that adult education had a large part to play in improving the quality of learning in City Beta. The data revealed that children whose parent or carer was participating in learning were less likely to become NEET, perhaps because of the example set of valuing learning, attending classes and doing homework. It was further agreed by the C3LP team that adult education needed to respond to the rapidly changing world through a curriculum review. There was a need for more literacy and numeracy classes and a demand for language classes for refugees. Adult education teachers attended an Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) training event and agreed to embed ESD within all their classes, as well as providing some new environmental classes about ‘Greening City Beta’. |

6. Fostering a culture of learning throughout life.

Cities can foster a vibrant culture of learning throughout life by organizing and supporting public events that encourage and celebrate learning; by providing adequate information, guidance and support to all citizens; and by stimulating them to learn through diverse pathways. Cities should also recognize the important role of communication media, libraries, museums, religious settings, sports and cultural centres, community centres, parks and similar places as learning spaces. In the city of Tunis, Tunisia, for example, socio-cultural events are held during Ramadan and promoted through different media channels, including newspapers, radio, television and the internet. Cultural centres, such as cinemas, music venues and local theatres, are also involved (UIL, 2017).

Fostering a culture of learning throughout life involves all learning modalities: formal, non-formal and informal. As explained earlier in this handbook, informal learning cannot be planned nor deliberately implemented, but it is possible to create conducive conditions. Public institutions in cities, such as museums, cultural centres and parks, can all be designed in ways that encourage informal learning by making it enjoyable and something to celebrate. This depends on engagement at the institutional level, where learning is celebrated through everyday activities. Celebratory events can also be organized in cities to foster a culture of learning, which is the case in many member cities of the UNESCO GNLC. For instance, the Irish learning city of Cork began hosting annual lifelong learning festivals each spring since 2004. The aim of these festivals is to promote and celebrate learning of all kinds across all age groups, abilities and interests, from preschool to post retirement. In the past years, the festival has grown to be a week-long celebration, and now includes more than 600 events, all open to the public and all free. It has also helped bring HEIs into contact with marginalized groups. Over the years, the festival has become an important part of life for citizens in Cork, with a variety of learning experiences available across the city (UIL, 2015).

|

Box 4.13. The City Beta story A member of the C3LP was invited to Ireland to attend the Cork Learning Festival. What an amazing celebration of learning! Full of excitement, at the next meeting of the C3LP she proposed that City Beta should hold its own Learning Festival. Partners were keen but saw some challenges: the first being how to pay for it. After a heated discussion in which every partner pleaded poverty, all the partners agreed to run their usual community events during the same week to start with and see how many events there would be. No special budget was designated, and partners contributed their usual learning resources. The college would run taster events across the city, the lifelong learning service of the municipality would run tasters for all their usual classes, and a large employer would run ICT taster events for older people. The second challenge was how would it be coordinated and publicized? None of the partners had run a city-wide learning festival before. They therefore contacted the coordinators of City Beta’s annual carnival, who provided invaluable advice about scheduling, attendance management, insurance and marketing. On their advice, C3LP held an initial meeting and invited everyone who ran learning events in the city – including large employers; further education and training providers; universities, museums and art galleries; the prison education service; groups of artists, dancers, crafters and musicians; beekeepers and historians; entrepreneurs and business trainers – to attend. The meeting was a success – suddenly, over 400 events were planned to run during the festival week. The third challenge was the weather, as it was unlikely that a week without rain could be planned. A local hospitality businesswoman was approached and asked to help. She offered to sponsor hired marquees for the whole city centre, which gave a colourful festival feel, provided cover when needed, and also provided excellent PR for her organization. The college art students designed and made advertising banners to hang from every lamppost and all the schools were provided with learning festival preparation packs. A musician composed a festival song which was learned by all the schools and musical groups. Many forms of learning were celebrated, from pottery, felting, stained-glass design, belly dancing, ukulele and guitar groups to history walks, creative writing, museum explorations, employee training events, entrepreneurship coaching, language learning tasters and ‘public engagement in science’ events by university staff. It was agreed by partners that it was important that every form of learning that was offered was included and celebrated. As a result, over 10,000 people in City Beta participated by attending a taster event, resulting in many new registrations for learning opportunities, and ensuring that the learning festival was a huge success in developing a culture of lifelong learning. |

These six focus areas set out some of the options available to policy-makers once a problem has been identified. They are usually the result of a dialogue or an interaction between experts, policy-makers and stakeholders. In the case of the learning cities model, the above six suggestions are an established roadmap based on experience and the observation of multiple interventions in different regions of the world.

|

Box 4.14. The City Beta story Having implemented the six interventions above, the C3LP held a meeting to consider their progress towards building a learning city. One of the C3LP members suggested that City Beta should consider making an application to join the UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities. At first, the C3LP members felt daunted, as they thought that, although City Beta was making great progress, there were still many challenges, and they didn’t feel that City Beta could claim to ‘be a learning city’ yet. The university could see that membership of a prestigious internationally recognized partnership with a focus on learning would be beneficial for university partnerships and international student recruitment. The city official responsible for education, together with a senior member of the university staff, contacted the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, which encouraged City Beta to apply for membership and directed the city representatives to the Guiding Documents of the UNESCO GNLC. These guiding documents explained that becoming a learning city is a process, not a state of being. The city official responsible for education gave a presentation at the next meeting of the C3LP, and it was agreed that the city would apply for membership to the UNESCO GNLC, to be coordinated by the local authority with support from the university. The first step was to map progress in the six interventions and then consider the three fundamental conditions for the implementation of lifelong learning in City Beta. |

Fundamental conditions for the implementation of LLL in learning cities

In addition to the six ‘focus areas’ that have been examined and which can be used as a framework for the design and implementation of policy innovations, the UNESCO concept of learning cities identifies three fundamental conditions for the implementation of the learning city model: (1) strong political will and commitment by the local government; (2) a participatory governance model involving all relevant stakeholders; and (3) the mobilization and use of resources.

1. Strong political will and commitment

To build a learning city and to ensure that its vision becomes a reality and is sustained over time takes strong political commitment. Local governments have the primary responsibility for committing political resources to realize a learning city vision. This involves demonstrating strong political leadership when developing and implementing well-grounded and participatory strategies for LLL, and consistently monitoring progress towards becoming a learning city. In many learning cities, local government representatives oversee the organization of projects linked to the learning city strategy, yet in the process, they cooperate closely with stakeholders from the private sector and civil society (UIL, 2017).

Ideally, the learning cities approach will not only benefit cities themselves but also promote lifelong learning and sustainable development throughout the whole country. The spirit of learning cities can spread as a best practice from one city to another and can lead to a country-wide initiative. National and provincial governments can promote and steer development of learning cities in their country actively through national policy-making, research support and dedicated resource allocation to learning cities. However, it is clear that achieving the wider benefits of learning cities needs strong political commitment, not only at the local level but also by regional and national decision-makers.

|

Box 4.15. The City Beta story City Beta’s mayor and the municipality were fully committed to the City Beta learning city initiative; however, a change of political leadership could impact on the C3LP’s plans. A meeting of the C3LP was therefore called, where its members agreed that the best method of securing the learning city initiative through any such change of leadership would be by embedding it within the city’s education and training policies. The municipality officers took this forward and secured a multi-party agreement that City Beta’s learning city development should be enshrined in city policy documents as an ongoing perpetual plan; this decision also meant that an annual budget would now be allocated to take City Beta’s learning city initiatives further. In order to apply to the UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities, City Beta had to gain the support of the National Commission for UNESCO. Three cities could be proposed for membership by the National Commission from each country in any application process. Representatives from the National Commission were invited to attend the City Beta Learning Festival and met the C3LP members to discuss the progress of the learning city. Many cities in the country were keen to apply for GNLC membership that year, so City Beta was delighted to be proposed by the National Commission in recognition of its development so far. |

2. Participatory and multi-level governance

To reiterate, building learning cities requires a multi-level governance approach founded on the strong political will of national, provincial and local governments. Based on the steadfast commitment of politicians and administrators, cities should enforce a participatory approach and include different voices in public decision-making, particularly by engaging in a continuous and open dialogue with civil society. Many local governments have developed strategies to enhance citizens’ participation in the decision-making and implementation processes, including participatory budgeting, neighbourhood committees, youth councils and e-governance solutions, among others (UN-Habitat, 2015).

|

Box 4.16. The City Beta story The City Beta Learning Partnership already had a wide range of learning providers, private sector employers, NGOs, and interested formal and non-formal institutions involved in its development plans. An observer from the regional government was also invited to get involved. Thinking about multi-level governance revealed that the city had not included citizens in the governance of the learning city. The C3LP therefore decided to establish Learning Neighbourhoods, which would each have a representative on a Learning Neighbourhoods Panel. Representatives from youth groups, ethnic minorities, migrants and women were encouraged to join, so that a cross-section of citizens became involved. The Learning Neighbourhoods Panel would have two representatives on the C3LP, one from the east side neighbourhoods and one from the west side. An annual award of funding for the development of a new programme of learning would be made to one Learning Neighbourhood from each side; it was agreed by the C3LP that the programmes of learning should have a theme of ‘strengthening citizenship’ and focus on human rights, peace education, Education for Sustainable Development, education for international understanding or a related topic to any of these. |

Relations between stakeholders can be vertical (between different levels of government, referred to as multi-level governance), horizontal (within the same level, for example between ministries or between local governments, referred to as cross-sectoral governance) or both. Partnerships with non-state actors, such as civil society organizations and the private sector, are also necessary for the achievement of common goals. Furthermore, urban governance should be gender-responsive and facilitate the inclusion and participation of youth, minorities and a cross-section of citizens.

|

Box 4.17. LLL in practice Participatory LLL governance in cities The City of Melton in Victoria, Australia, established the Community Learning Board (CLB): a governance mechanism that gives communities and organizations a direct influence on the design and supervision of lifelong learning strategies addressing social and economic issues. Members of the CLB are appointed for four years or for the duration of a Community Learning Plan, which is developed by the CLB to implement Melton’s learning city strategy. The CLB is usually chaired by the mayor and includes leaders from a variety of sectors: business and industry; NGOs and not-for-profit organizations (NPOs); employment services; state and independent primary and secondary schools; universities and vocational education providers; adult education; mature age learning; early learning; the health sector; disability education providers; community representatives; and the Victorian Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. A Melton city councillor, council’s chief executive officer, and key council managers and personnel relevant to the implementation of Community Learning Plan goals are also members. Source: UIL, 2015 |

3. Mobilization and utilization of resources

To implement LLL in learning cities, resource mobilization and utilization is key. Cities and communities that invest in lifelong learning for all have seen significant improvements in terms of public health, economic growth, reduced criminality and increased democratic participation. Encouraging greater financial investment in lifelong learning by government, civil society, private sector organizations and individuals is a central pillar to securing the means to build and sustain learning cities. This can be achieved through multi-stakeholder funding partnerships, cost-sharing mechanisms, match funding and sponsorships, and by linking to philanthropic or private-sector partners.

An example of cost-sharing mechanisms is demonstrated in Villa María, Argentina, where a multi-stakeholder partnership between institutes in the public and private sector has been established, each with their own budgets allocated to contributing towards the learning city project. To mediate fairness and representation between the multiple financial stakeholders in the project, a Learning City Council was created and later ratified by the municipal council. The Learning City Council is responsible for forming committees, planning actions encouraging lifelong learning in the city, and liaising with local forums such as activity and event groups and community liaison committees. Villa María’s cost-sharing approach to funding enabled a substantial increase in human resources, learning opportunities and representation of a wider range of sectors, including the education sector, production sector and community organizations (UIL, 2017).

The possibilities for mobilization and utilization of resources go far beyond cost-sharing mechanisms to include non-financial means, such as using all stakeholders’ resources as learning sites. These include cultural venues, libraries, restaurants and shopping centres, among others. This can bring learning closer to the people and ease access for everyone. Another way to use non-monetary resources is to invite citizens to contribute their talents, skills, knowledge and experience on a voluntary basis and to encourage the exchange of ideas, experiences and best practice between organizations in different cities. Contagem, Brazil, for example, has introduced a ‘community speaker’ project, which encourages community leaders to work together with staff from different city departments and private-sector bodies to promote the concept of LLL. To support the dynamic use of resources, universities share the cost of the community speaker project and provide rooms for conferences, meetings and workshops for public servants who are members of management committees (ibid.).

|

Box 4.18. The City Beta story The City Beta Learning Partnership identified that the development of skills in the city needed to change in order to enable citizens to access new employment opportunities in the future. They undertook a detailed ‘skills needs analysis’ of all current and nascent employment sectors in the city, asking for their views about future skills needs. Alongside this, the university, together with local TVET institutions, undertook horizon scanning to map potential areas of investment in the city and region in response to the development of renewable energy, zero-carbon and energy efficient building technologies, the circular economy, blockchain, artificial intelligence and health technology innovation, all sectors either developing or nascent in the region and developing areas of expertise within the university and Further Education College. The C3LP made a large funding bid to the national government for the intensive development of these new skills areas. The national government was impressed with the entrepreneurial leadership of the C3LP and agreed to fund the City Beta Skills Initiative as part of its regional development plan. The university and college established centres of excellence and free training in the skills needed to underpin each new industrial development. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed a need for health education and a healthier environment in the city. This was not just about the ways in which to prevent transmission, but also about how to improve healthy lifestyles for all citizens and reduce underlying health vulnerability. A Learning Neighbourhood Group was concerned about air quality and developed a cross-city air-quality monitoring project, which made representations to the C3LP. As a result, the university initiated a research project to reduce emissions of particulates by the major manufacturing plant on the east side edge of the city, working with international partners identified through the UNESCO GNLC who were tackling the same problem. The municipality created a park and ride to reduce traffic through the east side into the city, introduced car-free zones in the city centre, and increased the provision of cycle lanes and safe cycle parks. A project to ‘green’ City Beta was initiated by an environmental NGO and adopted with enthusiasm by the municipality. Landlords were given grants to create green roofs and walls on their city centre buildings and new green spaces were created by changing road designs and using planted areas to reduce water run-off and noise pollution. Public green spaces and parks were left to grow, creating areas of wildflowers and havens for wildlife. University staff started beekeeping in the university grounds and students built eco-huts for use in environmental education. Learning Neighbourhoods started community gardens, with enthusiastic uptake of vegetable and kitchen gardening. Adult education empowers learners and develops their confidence to be assertive and work collaboratively to address local needs. The adult education tutors had embedded Education for Sustainable Development in their curriculum, which raised awareness in learners in the east side about the risks associated with climate change. They formed a study circle (see Section 3.3.1) and became concerned about the potential problems of flooding in their community and the high levels of pollution in the river. The study circle expanded and eventually formed the ‘East Side Learning Neighbourhood Flood Prevention Group’, which contacted the national body for monitoring pollution and the municipality’s environmental officers. A vociferous meeting resulted in the promise of an action plan by the monitoring body to tackle the problem from upstream farming pollution. The municipality also responded to the suggestions of the group by working with the large employer on the east side bank of the estuary to create an artificial floodplain. A large area of land no longer needed by the employer due to the contraction of the industry was returned to wetland with overflow into the sea, reducing the risk of flooding on the east side. Community volunteers developed hides for watching birdlife as the wetlands became populated by wildfowl. These responses to sustainability issues had a direct relation to adult learning and demonstrate that learning can help to solve major problems for our communities. |

4.2.3. Building a monitoring and evaluation system

Designing a monitoring and evaluation system for policies aiming to achieve multiple goals, as in the case of learning cities, is certainly a complex task. While some monitoring models have been developed for learning cities, this is one of the areas in which more comparative research on good practices is still needed.

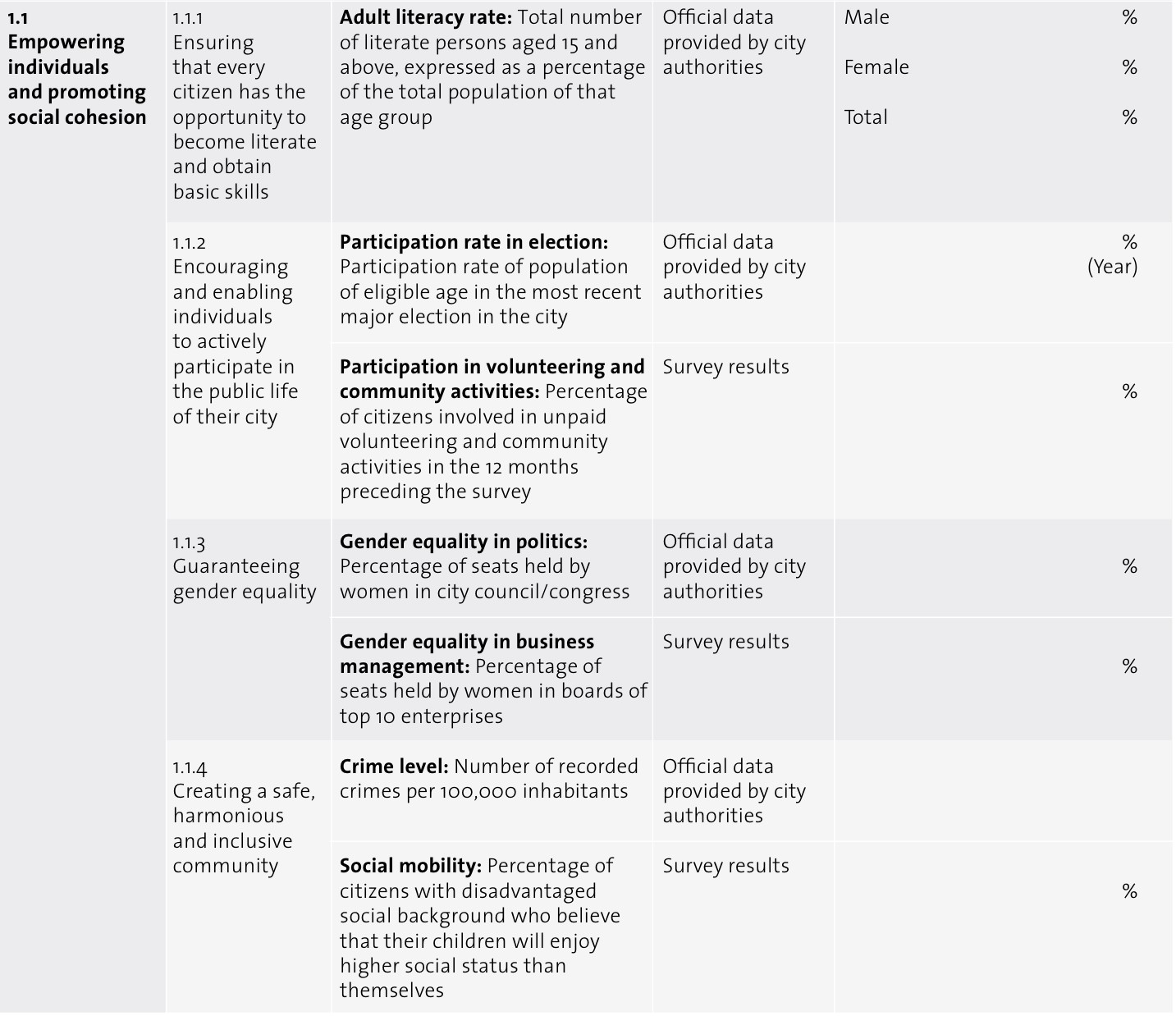

Since collected information will inform decision-makers for planning and accountability purposes, it is important to represent key processes and goals with reliable indicators and similar measurements. Additionally, monitoring and evaluation systems must correspond to considerations and goals defined in previous stages of the policy design process. Figure 4.1 is a list of key features and measurements developed by UIL (2015b) as an example of a monitoring and evaluation indicators system for a learning city. Although it includes only basic measurements on potential outputs, it identifies how broad goals are disaggregated into specific actions and how these actions are translated into specific goals to be achieved.

Figure 4.1. Monitoring and evaluation indicators

Source: UIL, 2015b

|

Box 4.19. LLL in practice Indicators and monitoring systems for LLL in cities There are attempts by UNESCO GNLC member cities to develop their own indicators and monitoring systems, as demonstrated by the learning city of Goyang (Republic of Korea), where a central learning city vision to facilitate and promote sustainable and inclusive learning, community participation and increased lifelong learning opportunities was recently established. These objectives lay the foundation for the development of Goyang as a lifelong learning city. In reference to the UNESCO GNLC’s Key Features of Learning Cities, Goyang adopts several domains, which focus on developing fundamental infrastructures, information, finance, organization and policy infrastructures. The indicators to measure these domains were developed using critically analysed rounds of public surveys by experts until a consensus of appropriate, reliable and relevant indicators were agreed upon. The data analysis of these domains is continuously monitored through qualitative evaluation systems, with the objective to ensure regular indicator refinement and review in line with the ever-changing times and regional characteristics affecting Goyang. In 2000, Beijing (People’s Republic of China) initiated its learning city development; since then, it has developed a comprehensive monitoring indicator system to support its goals. Examples of the quantitative indicators include measuring GDP per capita, the number of community elderly service institutions and facilities, and the annual participation rate of urban and rural residents in community education. Further to this, examples of the qualitative indicators include measuring the extensive publicity of the learning districts, the effective service of the construction of learning districts, and the promotion of regional development strategies. In 2020, the indicator data collected from the monitoring process was used to develop a report that summarized Beijing’s experiences and challenges, and which proposed suggestions for future improvements. This report was presented to the Beijing Municipal Commission of Education as a means to inform policy-making and to improve the city’s efforts. Beijing’s education departments have since worked to establish an information platform whereby indicator data collection and reporting can be shared effectively between district educational administrative departments and the Beijing Municipal Commission of Education. Additionally, city-based improvements in learning city planning and management have been seen across several of Beijing’s districts through incentives that encourage community participation and develop the infrastructure of the city. Sources: Goyang Research Institute, 2020; Beijing Academy of Educational Sciences, 2021 |

Beyond the availability of information, it is important to create conditions to promote the instrumental use of monitoring and evaluation – that is, to guarantee that any information can be used to support decisions. Policy-makers should consider how the information collected might be used by advocates to encourage widespread understanding and ownership of LLL as a philosophy and an approach. LLL policy-makers need to take a critical stance with regard to LLL initiatives to identify gaps or issues requiring attention. These could include ensuring safe learning environments for everyone, the digital divide (which can lead to the exclusion of some learners), the learning needs of people with disabilities, ensuring gender-sensitive teaching, and learning modalities and awareness of the difference between urban and rural access to learning. Leaders within educational institutions should work to produce an institutional strategy for lifelong learning as a document, succeeded by a collective effort to ensure that strategy’s implementation.

In addition, policy-makers must consider an increase in research activities focused on LLL by collaborating, cutting across different disciplines, and reflecting on how the interconnectedness of learning transcends traditional categories and boundaries. By supporting and disseminating research, HEIs can reinforce LLL not only locally, within the institution itself, but also nationally and internationally.

|

Box 4.20. The City Beta story One of the foundations for building a learning city is to develop monitoring and evaluation of progress. The City Beta Learning Partnership held a forum with evaluation experts from the university, college and municipality education service; the forum members agreed that an evaluation plan should be developed which measured progress against the SDGs in the city, including progress in promoting lifelong learning. A document from the UNESCO GNLC called Learning Cities and the SDGs: A Guide to Action provided invaluable guidance (see also Section 1.1.2). Taking this broad approach meant that, as partners of the C3LP, all institutions in the city would contribute to City Beta’s LLL goals, not just the education and training providers. The data collected could also be used to inform the government of the country about local progress against the SDGs. The more the members discussed the SDGs, the more they realized that their work in building a learning city had, in fact, been helping City Beta to become more sustainable. The C3LP agreed that this interrelationship would form the basis of a monitoring and evaluation system for learning city development, inspired by the model established by the city of Goyang, Republic of Korea (see Box 4.19). There are still many challenges to be faced in City Beta, including the likelihood of an increase in migrants and refugees coming to live in the city. Their reasons for coming to City Beta are manifold, including because of conflict in neighbouring countries, climate emergencies and climate change pressures, and economic migration. As noted in Box 4.2, the citizens of City Beta have a great reputation for being welcoming to those in need; it was therefore agreed by the C3LP that City Beta would not just react but proactively prepare for this increase in citizens. Looking at other members of the UNESCO GNLC for inspiration, the C3LP partners saw a similar response to refugees in Larissa, Greece, as well as in Swansea, UK. These two case studies inspired City Beta to welcome new citizens by planning for new homes, language support, school places and training opportunities for adults. The municipality therefore identified any vacant homes that could be renovated and made useful, while the Further Education College and the City Beta Learning Partnership planned additional programmes for language learning. Finally, the health authority ensured that counselling support would be available in case refugees had suffered traumatic events. The C3LP realized that its experience in developing systems for the RVA of non-formal and informal learning outcomes would be useful, as many refugees will have lost their documentation during their journey. The university offered to run a qualifications recognition service, so that highly qualified refugees with qualifications gained abroad could quickly gain recognition and employment. Most importantly, an appeal through the Learning Neighbourhoods met with an immediate warm response from citizens and the offer of clothing and household items. The rural areas around City Beta lack facilities for cultural pursuits and there is rural poverty in many districts, so extending the learning city to encompass the region is part of the development plan. This approach has been undertaken by the UNESCO GNLC member city of Trieste, Italy. Transport continues to be a problem in City Beta, however, and the infrastructure for a change to electric vehicles is not yet available. One idea is to create aerial routes over the city for pedestrians and cyclists, but feasibility studies need to be undertaken, as winds have been very high in recent climate events. The learning city of Medellín, Colombia, has created a train network that crosses the city in four directions and then reaches up into the mountainous rural areas using funicular railways and cable cars, ensuring that all communities can reach the city centre at low cost, thereby accessing jobs and education. City Beta does not have steep hills but does have communities on the east side who are disconnected by lack of affordable public transport. An electric tram or similar may be the answer, but the main challenge is how to reduce the cost for passengers. Renewable energy is seen as another opportunity for investment, and the city is considering how to develop this with as little impact on citizens’ daily lives as possible. Research by the university has become a key part of City Beta’s learning city initiative and helps the C3LP to make informed decisions and feasible plans. Measuring progress against the SDGs highlighted the huge impact that City Beta’s learning city initiative has made on addressing the imbalance between the east and west sides of the city as well as the immense progress City Beta has made against SDG 4. Seeing progress being made is a great motivator for further endeavours, so the municipality decided to hold a learning city celebration for all citizens, uplifting spirits after a challenging couple of years. Moreover, City Beta was informed that it had been accepted into the UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities. There was great excitement in the C3LP, and the news was announced at the start of the second City Beta Learning Festival, so that celebrations could be city wide and community deep. Because of continued restrictions due to COVID-19, the celebration was outdoors; yet it was accessible for all and free to enter. The city decided to provide a music and lights display, using the sea as the background and ensuring that all citizens could see it from their homes. This was a popular decision and may be repeated in future years, as City Beta continues to make progress in developing into a learning city. |

4.2.4. Learn by doing: Continuously improving as a learning city

The LLL policy process means engaging in continuous policy improvement, i.e. learning lessons from policy design and implementation and taking account of how public problems and contextual factors are constantly evolving. In the case of the learning city model, this means retaining the idea that ‘learning city status’ is not reached by a prescribed list of interventions. As explained in the network’s guiding documents, building a learning city ‘is a continuous process; there is no magic line over which a city will pass in order to become known as a learning city’ (UIL, 2015b, p. 9). Fundamentally, for stakeholders involved in the implementation of the learning city model, recognizing this ‘continuous process’ underpins policy refinement. Finally, since the policy process is dynamic and nonlinear, steps to ‘refine’ a policy do not mean that the cycle is complete: revisiting previous stages is always advisable.

This chapter began by exploring LLL in urban areas before introducing a teaching case, City Beta, a succinct exercise in applying the handbook’s guidance on national LLL policy-making and the design of LLL implementation strategies. The City Beta case demonstrated the LLL policy-making process in concrete terms and revealed how considerations relevant to the design of LLL implementation strategies can be applied to a specific LLL policy. A similar approach can be used for other LLL policies – regardless of the targeted level of implementation – to make the guidance provided in this handbook relevant to any national context.

LLL policy-making and implementation through the learning city model

Bardach, E. 2000. A practical guide for policy analysis: The eightfold path to more effective problem solving. New York, Chatham House Publishers, Seven Bridges Press.

UIL (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning). 2015. Communities in action: Lifelong learning for sustainable development. [Online]. Hamburg, UIL. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000234185 [Accessed 21 April 2020].

UIL. 2015b. Guidelines for building learning cities: UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities.[PDF] Hamburg, UIL. Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002349/234987e.pdf [Accessed 20 April 2020].

UIL. 2017. Unlocking the potential of urban communities. Volume II. Case studies of sixteen learning cities. [online] Hamburg, UIL. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000258944 [Accessed 20 April 2020].

UIL. 2017a. Learning cities and the SDGs: A guide to action. [PDF] Hamburg, UIL. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260442/PDF/260442eng.pdf.multi [Accessed 20 April 2020].

UIL. 2021. Snapshots of learning cities’ responses to COVID-19. [PDF] Hamburg, UIL. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378050 [Accessed 2 July 2021].

UN DESA (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs), Population Division. 2018. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Jan/un_2018_worldcities_databooklet.pdf [Accessed 14 December 2021].

UN-Habitat. 2015. HABITAT III Issue Papers 6 – Urban governance. [online] New York, United Nations Task Team on Habitat III. Available at: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/habitat-iii-issue-papers-6-urban-governance [Accessed 23 February 2022].

UN-Habitat. 2020. World cities report 2020: The value of sustainable urbanization. [PDF] Nairobi, UN-Habitat. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/10/wcr_2020_report.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2021].

Watson, C. and Wu, A. T. 2015. Evolution and reconstruction of learning cities for sustainable actions. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 145, pp. 1–19./p>

WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2017. Statement of the WHO European Healthy Cities Network and WHO Regions for Health Network presented at the Sixth Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health Ostrava, Czech Republic, 13–15 June 2017. [PDF] Ostrava, WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/343202/HC-RHN-Statement-Ostrava-final-as-delivered.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 20 April 2020].

WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2018. Copenhagen Consensus of Mayors. Healthier and happier cities for all. A transformative approach for safe, inclusive, sustainable and resilient societies. 13 February 2018, Copenhagen, Denmark. [PDF] Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/361434/consensus-eng.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 20 April 2020].

World Bank. 2020. Poverty. [online] Washington D.C., World Bank Group. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview [Accessed 21 April 2020].